Examining the Gap Between Gross Revenue Retention and Net Revenue Retention

August 1, 2023

The average difference between Gross Revenue Retention and Net Revenue Retention (which is equal to or greater than Gross) – aka, the GRR-NRR Gap – is a bit more than twelve percentage points. That is: most companies we observe are able to upsell and cross-sell enough that their NRR exceeds their GRR by 12 points; if an average company had 85% GRR, we would expect their NRR to be 97%.

The math here isn’t sophisticated; it’s just subtraction. Be sure you’re using the same period for both, and calculate the Gross and Net revenue retention following our how-to template, which you can find here.

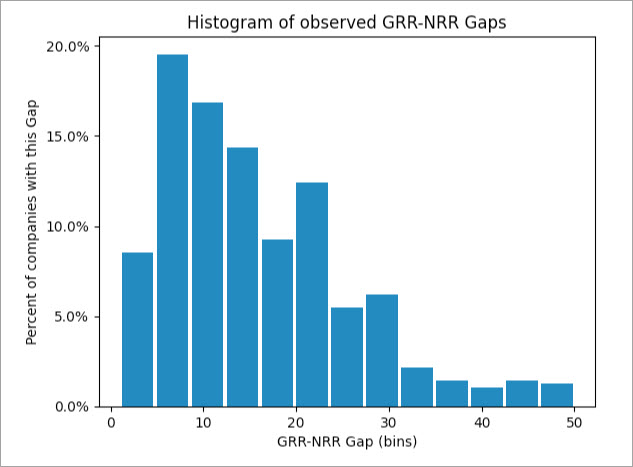

Very few companies report a GRR-NRR gap exceeding 30 percentage points. You can see the rapid drop-off in the histogram below: a lot of gaps below 20 points, a fair number with a difference between 20 to 30 points, and very few with a gap above that. (We excluded a handful that reported a gap over 50 points).

A range of 8-20% is a fairly normal range for a GRR-NRR gap. Measuring a smaller (narrower) gap, or a larger (wider) gap, can often suggest what’s going on inside a company – and some possible room for improvement.

Companies With a Narrow GRR-NRR Gap

A narrow GRR-NRR gap (under 5%) is a strong sign that upsell and cross-sell are weak. Fewer than 10% of companies report a GRR-NRR gap under 5%. (By definition, NRR must be equal to or greater than GRR, so 0% is a hard floor.)

Several companies in the survey report identical GRR and NRR and we have encountered a few examples during our day-to-day jobs reviewing company financials for underwriting MRR-based credit facilities. Speaking with one prospect we discovered that this founder-run company had excellent gross retention, but simply never bothered to upsell existing customers. Furthermore, they had only one fixed-price package to sell, making upgrades or usage-based pricing growth impossible.

If you aren’t upselling simply because you don’t upsell, that’s an unforced operational error. Good SaaS operators will be running customer success programs to make sure customers receive increasing value from the product, and also running account management to continually capture part of that shared, growing value.

If, however, you aren’t upselling because you can’t raise prices or entice additional usage from existing customers – without scaring them off to a competitor or substitute – that’s a bad sign for the depth and stickiness of your value proposition. Companies in this corner need to find a way to make themselves deeper and more differentiated, to avoid commoditization and price pressure.

Another source of price increase is inflation adjusters in contracts – understandably neglected, perhaps, because the period 2009-2021 saw both historically low inflation and the rise of the SaaS business model. But the experience of 2022, when inflation briefly hit 9% annualized, should remind everyone that price stability isn’t a given, and SaaS providers have to “keep the lights on,” too.

Companies With A Wide GRR-NRR Gap

A particularly wide GRR-NRR gap (over 20%) isn’t necessarily unhealthy, but it is somewhat abnormal.

Sometimes, particularly if GRR is already quite healthy (90%+ for enterprise, or 80%+ for SMB), a wide gap can be a sign that upsell is very effective and/or that a “land-and-expand” strategy is working. In that case – keep it up!

Other times, such as when GRR is weaker, a wide gap can arise from a “rotation” of customer profile. For example, when a company re-focuses on an Ideal Customer Profile (ICP), it often results in “non-regrettable churn” as customers outside of the ICP choose not to renew. That loss of non-ICP customers, combined with a deeper focus on retaining and upselling ICP customers, can lead to a large GRR-NRR gap.

A very wide gap, above 30%, is rare but not unheard of. It’s usually a sign that some kind of one-off has occurred (such as losing a big customer or upselling a “whale”) or that the go-to-market strategy is highly imbalanced. For example, a product that is dramatically underpriced but follows up with a usage-based upsell strategy might exhibit a very wide GRR-NRR gap. In that case, a SaaS operator should consider bringing forward the “upsell” revenue into the first-year contract value by increasing the initial entry price – provided that the sales close rate won’t take too much of a hit.

A very high GRR-NRR Gap can be unhealthy, however. This is when one or only a few customers consume increasing amounts of the product, while the majority of customers do not. As this sequence plays out, it can initially seem like a great thing, but eventually, if it carries on too long, it can introduce significant customer concentration into the revenue model. Eventually, a heavily concentrated SaaS company may become “captured” into more of a consulting-type company, catering its roadmap and features to the whims of one or few customers, while the rest of the user base remains small, disengaged, and ignored. To be clear: going the other way – building the platform with one or a few anchor customers who guide feature development and help “fund” the early versions of the platform – is a terrific way to build a SaaS business, and we have provided growth debt to many such companies. The key to owning your own destiny as a true SaaS product company is to gradually diversify the customer base, not the reverse.

Final Note on Measurement Fidelity in Retention

One scenario we’ve encountered, particularly when a SaaS company is delivering a service (particularly one attached to a device or location) is that activating and deactivating subscriptions on a per-device basis can lead to misleadingly low gross retention numbers and a correspondingly large gap. It makes GRR seem low (because “deactivated” devices were dropped off) and makes NRR seem high (because “reactivated” devices looked like upsells when they were turned back on).

Evaluating the GRR-NRR gap for a company with this sort of measurement wrinkle, therefore, requires understanding the context, and acknowledging that the gap may be larger in this sort of situation. Still, a gap of 0 tends to be unhealthy and a gap larger than peers experience is probably also a flag.

In Conclusion

It’s a rarely-discussed thing, but the GRR-NRR gap can be a useful “sanity check” on a SaaS company’s metrics, and when it falls outside of the usual range, can give a hint to operators and investors as to when something might need tweaking.

Our Approach

Who Is SaaS Capital?

SaaS Capital® is the leading provider of long-term Credit Facilities to SaaS companies.

Read MoreSubscribe