Considering the “Unprofitable” SaaS Model

August 20, 2013

(Are we really still having this conversation?)

There have been a few articles lately about unprofitable SaaS businesses going public. The general theme of theses articles seems to be that there is a new “bubble” is upon us, and fundamentally flawed businesses are going public.

One such recent post “The Unprofitable SaaS Business Model Trap” was sent to me by several colleagues with the introduction of “you probably already know this but…” After reading it several times, I must admit, the article is well written, and made several very good points. However, the main thrust of the article – which focused on how marginally profitable the SaaS business model is – was fatally flawed by one bad assumption.

Getting a Grip on Customer Retention

In the author’s example, he assumed a “great retention rate” was 75% per year. Based on this assumption he correctly pointed out that for every $1 of first year revenue generated from a group of customers, the business will ultimately generate $4 of revenue over the customer-life of that group. He then goes on to describe how sales, marketing, support, and development cost consume almost all of the $4 of revenue.

The main flaw is not the author’s logic, but rather the 75% revenue retention assumption. SaaS Capital has looked in detail at the retention rates of hundreds of SaaS Companies and also surveyed hundreds more on this specific topic. Both the observed and reported average revenue retention rate for an enterprise SaaS company is 90%. It’s a little lower for companies serving small businesses, and higher for SaaS companies serving the fortune 1,000. We won’t lend money to folks lower than 85% retention.

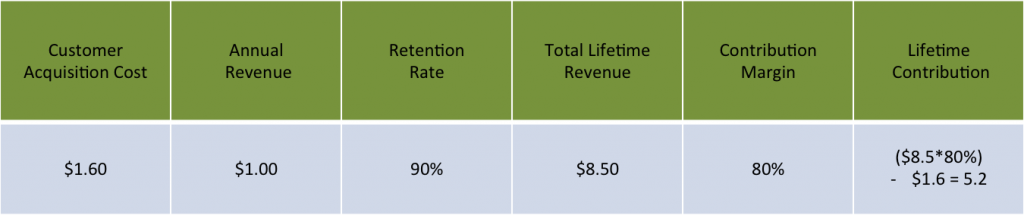

The difference between 75% retention and 90% retention is HUGE. Just consider, the $4 dollars of lifetime revenue referenced above turns into $8.5 dollars of lifetime revenue if the retention rate is 90%. Therefore, the same group of new customers will generate over twice the revenue over time with a valid 15% up-tick in retention.

The impact on profitability is even higher. To support an extra $4.5 dollars of revenue, the company barely needs to lift a finger. The only marginal costs that are required to support this revenue includes (maybe) a few more servers, some added bandwidth, and a customer support person or two. A very conservative contribution margin for theses existing customers would be 80%.

Average Costs vs. Marginal Costs

The one other flaw in the analysis is the use of “Average Costs” to calculate unit economics. Pushing R&D spending and administrative costs down to the customer level makes for bad decisions. Are customers really unprofitable if they do not generate enough revenue to cover “average” R&D and administrative costs? Would the business become more profitable if all theses “unprofitable” customers left? The answerer is no, the business would shrink and becomes less profitable.

Conversely, let’s consider what happens when the business signs-up a bunch of customers that have high contribution margins, but do not cover “average” R&D and administrative costs. In this scenario, the “average” costs will go down, and the company makes more money, not less. Therefore, we recommend that the variable/marginal costs are the items that should be considered at the customer profitability level versus average costs.

So, back to our analysis of the original article. When we look at substituting 90% retention for 75%, and consider contribution margin instead of “average total costs”, we have a much better look at real profitability: a customer that costs $1.60 to acquire and contributes $5.2 over its lifetime to be spent on R&D, overhead, and profits. On a percentage basis, the $5.2 equates to about 60% of revenue which is more than enough to cover theses costs and then some.

From a P&L perspective, however, the first year is ugly. Most of the $1.6 in customer acquisition cost will get recognized up front, but on average, only ½ of the first year of revenue. Adding in the cost to support the revenue (20%), the first year loss on the deal is: $.5 (revenue) less $.1 (COGS) less $1.6 (customer acquisition costs). A $1.2 loss on $.5 in revenue. Add a healthy growth rate generating lots of new customers and this is loss generation machine.

In the following years, however, the combined revenue will be $7.5 against combined costs of $1.5.

In closing, I have no idea if Marketo, the subject company of the original post is a “buy” or a “sell”, and I also do not know its retention rate. That said, if it is retaining customers and maintaining incremental costs at anywhere near the SaaS industry average, heavy GAAP losses should not be a big concern.

Our Approach

Who Is SaaS Capital?

SaaS Capital® is the leading provider of long-term Credit Facilities to SaaS companies.

Read MoreSubscribe